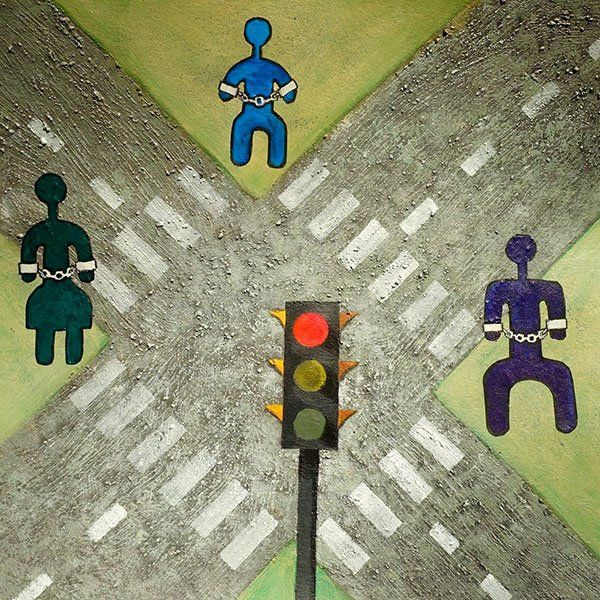

ver the past decade, many states have increased their abilities to serve victims of human trafficking. For example, in Minnesota, state law and funding priorities have focused particularly on the needs of sexually exploited and trafficked youth under age 25 through the Safe Harbor program, while more recent legislation as well as federal grants have increased awareness of labor trafficking and exploitation

cover story one

Responding to Human Trafficking Victims

Core Competencies for Health Care Providers

Caroline Palmer, JD

None of this activity would be possible without a robust multidisciplinary approach. Health care providers, specifically, have enhanced the scope and competency of Minnesota’s response, which spans across state agencies (health, human services, and public safety), tribal nations, nonprofit organizations, and various systems.

Health care providers play a critical role in identifying and assisting human trafficking survivors. Whether seen in an emergency room, community clinic, dentist’s office, or treatment center, survivors seek care from several different medical and behavioral health professionals, yet these providers may not always know that their patients or clients are suffering from, or are at risk of, trafficking or exploitation. Survivors are often hesitant, ashamed, or even fearful when it comes to sharing details beyond what is necessary to meet their immediate health care needs.

For these and many other reasons, experts from around the United States were summoned by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office on Trafficking in Persons for a three-year-process to develop a set of “core competencies” to better identify and respond to the health care and behavioral health needs of human trafficking survivors.

Survivors are often hesitant… when it comes to sharing details.

These core competencies were designed with four key constituencies in mind: Individual practitioners, health institutions or organizations, researchers, and health educational institutions. HEAL Trafficking, the International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children, and the National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners were key partners along with the National Human Trafficking Training and Technical Assistance Center in this project. The report, “Core Competencies for Human Trafficking Response in Health Care and Behavioral Health Systems” was released earlier this year and is available on-line.

Summarizing the Core Competencies

The core competencies, which the report defines as “skills needed for professionals to most effectively conduct their work,” were developed according to a set of guiding principles based in public health approaches. These approaches include prevention; trauma-informed, culturally responsive, and patient- or client-centered practices; promotion of individual agency and empowerment; holistic responses; coordination across disciplines for wrap-around services; and referrals to appropriate service providers. So too, the core competencies take into account other factors such as access to quality health care; societal or environmental influences; relationships with other disciplines including law enforcement, child protection, and legal services; and conscious or unconscious biases held by providers. There are six core competencies and one universal competency outlined in the report, briefly described below:

Universal Competency: Use a Trauma and Survivor-Informed, Culturally Responsive Approach

The universal competency of using a trauma and survivor-informed, culturally responsive approach is considered an “umbrella framework” for all of the other competencies in the report. Trauma-informed care is focused on building trust and rapport with patients or clients while recognizing that trauma experiences, including racial, cultural, and historical trauma, determine willingness or hesitancy to disclose harm. Policies and practices should include informed consent for all aspects of patient or client care and intake or screening protocols that do not cause further harm.

Organizations and institutions must ensure that their professionals are well-trained in trauma-informed approaches. Further, supports should be in place for professional responders in the event of vicarious trauma and burn-out that can come from serving individuals and populations experiencing extreme trauma like human trafficking.

In terms of research and education, universal competency promotes multidisciplinary-focused research strategies designed to identify health disparities and develop innovative approaches to care provision. Educational settings should strive to equip students with trauma-informed approaches to identifying human trafficking survivors while also giving them the tools they need to identify their own vicarious trauma resulting from service provision.

Finally, universal competency promotes the active engagement of persons with lived experience in human trafficking in advisory and leadership roles both on the direct-care and organizational or institutional levels as well in the development or delivery of curriculum. Researchers should strive to create partnerships with persons who have lived experience and fully integrate their expertise into all aspects of research design and delivery.

This engagement of persons with lived experience dovetails with the priority of ensuring all efforts to respond to human trafficking, whether in direct care or through institutional policy, research, and education, are culturally responsive, driven by cultural humility, and inclusive of all races, genders, sexual orientations, ethnic and religious groups, and abilities.

Understand the Nature and Epidemiology of Trafficking

Competency 1 uses a social-ecological model to demonstrate the connections between society, community, relationship, and individual dynamics in responding to human trafficking. In so doing, this competency recognizes the dynamic interplay of activities that encompass trafficking and exploitation (sex and labor), as defined under law as well as through policy and practice. This competency supports research that looks at the distinctions between sex and labor trafficking (as well as their interrelationships) and promotes integration of human trafficking curriculum in all levels of education, and particularly for future health care and behavioral health professionals.

In terms of trafficking and related social determinants of health, Competency 1 highlights the many economic, cultural, and social contexts that enhance trafficking risks, including adverse childhood experiences, poverty, racial inequities, homelessness, disabilities, mental illness, migration, and more. The competency promotes understanding of risk/protective factors in direct services, organizational and institutional policy, research approaches, and curriculum.

Evaluate and Identify the Risk of Trafficking

Competency 2 underscores the concept that disclosure of trafficking is not the goal of an interaction with a survivor; instead, screening tools should be tailored toward detecting indicators (sometimes referred to as “red flags”), tailoring care based on these indicators, and making appropriate referrals. These tools are most effective when evaluated for their reliability and even validated.

When the focus is taken off of a disclosure (which can feel like pressure to a patient or client) and directed toward identifying risks, creating harm reduction and safety plans to reduce risk, and building trust and rapport, it is more likely that a survivor will feel comfortable seeking help either in the moment, or at a future time, from the provider.

Risk assessment is most effective when a patient or client is assured that they are in a confidential setting. Any instances of when confidentiality is broken (such as mandated reporting) should be explained up front so the patient or client can make informed decisions about what to share. Organizational and institutional policies should be written in the strongest terms to protect information gathered from patients and clients. So too, researchers and educators should seek to promote concepts around confidentiality and autonomy as part of trauma-informed and patient- or client-centered practices.

Providers can connect clients with community-based services.

Evaluate and Identify the Risk of Trafficking

Competency 2 underscores the concept that disclosure of trafficking is not the goal of an interaction with a survivor; instead, screening tools should be tailored toward detecting indicators (sometimes referred to as “red flags”), tailoring care based on these indicators, and making appropriate referrals. These tools are most effective when evaluated for their reliability and even validated.

When the focus is taken off of a disclosure (which can feel like pressure to a patient or client) and directed toward identifying risks, creating harm reduction and safety plans to reduce risk, and building trust and rapport, it is more likely that a survivor will feel comfortable seeking help either in the moment, or at a future time, from the provider.

Risk assessment is most effective when a patient or client is assured that they are in a confidential setting. Any instances of when confidentiality is broken (such as mandated reporting) should be explained up front so the patient or client can make informed decisions about what to share. Organizational and institutional policies should be written in the strongest terms to protect information gathered from patients and clients. So too, researchers and educators should seek to promote concepts around confidentiality and autonomy as part of trauma-informed and patient- or client-centered practices.

Evaluate the Needs of Individuals Who Have Experienced Trafficking or Individuals Who are at Risk of Trafficking

Competency 3 underscores the importance of engaging the patient or client in shared decision-making when developmentally appropriate. For trafficking survivors, many of whom have had their sense of control stripped away, the ability to participate in – and even lead – decision making is a critical part of healing. Creating an individual plan of action, especially in partnership with a trusted health care or behavioral health provider, can give a survivor options where they did not have them before.

This competency also promotes the importance of a multidisciplinary teams approach bringing together health care, behavioral health, law enforcement, public health, social services, the legal system, schools, and other organizations, as well as persons with lived experience, to develop protocols for responding to the needs of survivors. These teams can conduct needs assessments of community resources that span from individuals to organizations and institutions and identify critical gaps. Such assessments can be created in partnership with researchers and educators to ensure that they are not only rigorous in methodology but also specially tailored to different populations, sustainable, and supported by training for all involved.

Provide Patient- or Client-Centered Care

Competency 4 promotes patient or client-centered interviewing practices, which span from the setting in which the interview occurs to the parameters of informed consent, the types of questions asked, and the availability of professional language interpreters. Centering the patient or client entails meeting them where they are – using age-appropriate language, being aware of trauma responses or triggers, collaborating on a care plan, explaining procedures, ensuring safety, and promoting informed consent by explaining confidentiality protections as well as mandated reporting requirements.

Organizations and institutions can support these direct service interactions by writing clear policies and procedures and ensuring that all staff are trained to follow them. Case review may be helpful to address complex situations or to provide learning experiences. “No Wrong Door” access to health services will ensure that policies and training give staff the ability to meet the needs of a survivor no matter where they seek help; this may entail adjusting service provision in the moment or making a warm hand-off to more appropriate services. Researchers and educators will benefit from this knowledge in terms of better understanding survivor needs, the efficacy of team approaches, and promoting effective ongoing training for professionals.

Trafficking survivors are resilient – they have many strengths that can be leveraged into their care plans, ensuring they receive assistance most apt to meet their needs. It is crucial that health care and behavioral health specialists actively engage survivors in recovery and healing, a process that can last a lifetime.

Use Legal and Ethical Standards

Competency 5 underscores protection of legal rights of trafficking survivors. For example, mandated reporting (for child or adult protection) may be required when a youth or family is involved. The patient or client should be informed about a mandated reporter’s responsibilities. Mandated reporting can also change the relationship with the patient or client, particularly if the patient or client feels betrayed by the health care or behavioral health specialist inviting intervention of systems like law enforcement, child protection, or adult protection.

Organizations and institutions should have clear policies in place for how and when mandated reporting occurs as well as how patients and clients are informed about reportable events; so too, educational programs should explain the different forms of reporting. Researchers may want to engage in further study about how mandated reporting influences the delivery of health care or behavioral health services.

Other legal considerations include HIPAA, patient consent compliance, health care record protections, ICD-10 documentation of trafficking in patient records, patient rights laws, minors consent to health care laws, victim rights laws, consequences of immigration status, parental rights, and much more. It is not incumbent upon all health care or behavioral health practitioners to know how to respond to every legal issue but they should have a clear idea about where to find resources, how to address certain situations without causing harm, and where to access educational materials for patients and clients.

Integrate Trafficking Prevention Strategies into Clinical Practice and Systems of Care

Competency 6 promotes prevention as part of any public health strategy to address human trafficking. A primary prevention focus, for example, includes screening for adverse childhood experiences and the social determinants of health, implementing knowledge of parenting and child development, and connecting patients and clients, as well as their families when appropriate, with community resources that address the risk factors for human trafficking and perpetration. Organizations and institutions are encouraged to develop training to raise staff awareness about the relationship between violence and health, as well as the intersections of human trafficking with other forms of harm such as domestic violence, sexual violence, and child abuse. Researchers and educators should integrate elements of health disparities, health equity, and the social determinants of health into their efforts.

In terms of secondary prevention, providers should apply concepts of risk and harm reduction in work with individuals currently experiencing human trafficking or exploitation. All staff and providers should have training on how to help patients and clients work to reduce risk – and such training and approaches should be made without bias or judgment. In addition, providers can connect clients with community-based services to support basic needs. Researchers can amplify the importance of risk reduction models and strategies for survivors of trafficking while educators can incorporate risk reduction concepts into curriculum.

Finally, tertiary prevention focuses on long-term strategies, sustaining health and safety planning for patients and clients, and continuing to address protective factors and resiliency strategies with patients to reduce further trafficking and exploitation. This approach requires a long-term commitment to quality health care access, research into effective aftercare and support services, and education about the long-term recovery needs of trafficking survivors – all informed by the wisdom of persons with lived experience.

Minnesota Efforts

The Minnesota Department of Health is in the process of developing state-specific human trafficking training for health care providers based on input from practitioners and survivors for release later in 2021. Input is welcome in the development of this curriculum. Please contact caroline.palmer@state.mn.us if interested.

Caroline Palmer, JD

is Safe Harbor Director, Injury and Violence Prevention Section, Minnesota Department of Health.

What is human trafficking?

Human trafficking is the sale of a person for the purpose of sexual acts or forced labor. Minnesota law uses the following definitions:

- Sex trafficking – receiving, recruiting, enticing, harboring, providing, or obtaining by any means an individual to aid in the prostitution of the individual; or receiving profit or anything of value, knowing or having reason to know it is derived from an act (of sex trafficking).

- Labor trafficking – recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, enticement, provision, obtaining, or receipt of a person by any means, for the purpose of debt bondage or forced labor or services; slavery or practices similar to slavery; removal of organs through the use of coercion or intimidation; or receiving profit or anything of value.

Report suspected human trafficking

- If you or someone you know is in immediate danger of being trafficked, call 911.

- To report a suspected trafficking situation, call the National Human Trafficking Hotline at 1-888-373-7888, send the text HELP to 233733, call the BCA at 1-877-996-6222 or email bca.tips@state.mn.us.

Victim resources

- Safe Harbor Minnesota connects trafficking victims with support services. Get information online or by calling 1-866-223-1111.

- The National Human Trafficking Resource Center provides a map-based list of victim resources. Information can also be obtained by calling 1-888-373-7888.

Human Trafficking Investigators Task Force

The Human Trafficking Investigators Task Force is led by the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension with assistance from metro area sheriffs and police, Homeland Security Investigations and the Ramsey County Attorney’s Office.

Task force members work with more than two dozen agencies to identify incidents of human trafficking and apprehend and aid in the prosecution of such crimes.

Criminal justice agency resources

Task force members and affiliate agencies are specially trained to investigate human trafficking crimes. Contact the BCA at 651-793-7000 for assistance with a human trafficking investigation.

BCA Training and Auditing also provides advanced training and support to local agency personnel.

MORE STORIES IN THIS ISSUE